Maybe you’ve seen some recent news articles about children with genetic diseases. Or maybe someone in your family has a child with a genetic condition. Diseases like Tay Sachs, Cystic Fibrosis or Sickle Cell Disease might ring a bell. And you might be wondering what the chances are that you could have a child with a genetic disease.

The purpose of this post is to provide you with information about what it means to be a “carrier” of a genetic condition, what your options are for testing, and what you can do about it if you discover you are a carrier of a genetic disease.

We have two copies of every gene. One copy comes from your mother, the other from your father. Genes are the instructions for the body – they tell our bodies everything from how big our feet should be, to what color our hair should be, to how to digest our food, and everything in between. We all have mutations, or changes, in our genes. It’s what makes us unique from each other. Some mutations have absolutely no effect on our health whatsoever, but, in some cases, a mutation can lead to disease.

If you are a “carrier” of a genetic disease, this means that you have a mutation in one of your two copies of the gene associated with that disease. So, if you are a “carrier” of Tay Sachs Disease, that means that of your two copies of the gene associated with Tay Sachs Disease, one copy has a mutation. That mutation causes the gene to be dysfunctional, and, as an effect, the body cannot understand the instructions that the gene is trying to provide and can’t perform its duty. But, as a “carrier”, you have a second copy, perfectly functional, and able to provide the body with the necessary instructions. So, for you as a “carrier”, you are healthy, you do not have that disease.

If you have a child with someone who is a carrier of the same disease as you, then you have a risk of having a child with that genetic disease. Why? Because if the child inherits the mutation copy of the gene from BOTH of you, he or she will have no working copies of that gene, neither copy will function to provide instructions for the body, and disease will occur.

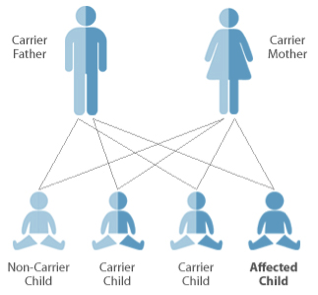

Image :http://www.jewishgeneticdisordersuk.org/index.php?/jewish_genetic_disorders/introduction_to_genetics

Above, you see a picture of two parents who are carriers. In each pregnancy that this couple has, there are 4 possible outcomes for their child. In one instance, the child has inherited both working, non-mutation genes from each parent (non-carrier child), in two instances, the child has inherited a mutation copy from one parent, and a non-mutation copy from the other parent (carrier child), and in one instance, the child has inherited both mutation copies of the gene and is “affected”, meaning that s/he has the disease. So, statistically, in a couple who are BOTH carriers of a genetic disease, there is a ¼ (25%) chance IN EACH PREGNANCY, that the child will have the disease. If only one parent is a carrier, there is no risk that the child will have the disease, but children can be carriers, which will be important for them to know when they are older and ready to have their own children.

So, how can you find out if you are a carrier of a genetic disease? There is genetic screening available. There is screening available that is ethnicity-based because certain ethnic groups are more likely to be carriers of certain conditions. For example, if you are Jewish, there is a group of diseases for which you’re most likely to be a carrier. If you don’t know your ethnicity, or if you’re mixed, or if you want extra screening, there are broad “Pan-Ethnic” screening options available.

What if you are found to be a carrier? The first step is to get your partner tested to find out if he or she is a carrier of the same condition. You should also inform your family members that you are a carrier. If you are a carrier of a genetic condition, that mutation is running in your family, so other family members may want this information and can get tested.

What if you and your partner are both found to be carriers? Well, now you have some decisions to make:

- You can get prenatal testing as early as the end of the first trimester to learn whether or not the baby will have the disease. You can find this out in order to prepare yourselves for a child who will have special needs, or you may choose to end the pregnancy.

- You can use In-Vitro Fertilization to create embryos outside the body, do genetic testing on the embryos, and then only implant the ones who do not have the disease. This is an invasive process, and can be expensive.

- You can use donor eggs or sperm, or choose to adopt.

More questions? Want to get screened? Give me a call, and we can make a plan for your family.